In Canada, there were 417,300 registered apprenticeships in 2016 (Statistics Canada, 2018) and registrations have grown over 200% since the 1990s (Statistics Canada, 2017). Trades education is growing and with it the number of workers in the market. As an apprentice progresses through their education, they face two problems. First, the challenge of maintaining and curating any resources throughout their time in a classroom setting and second, showcasing their hands-on skills.

To solve these problems, this article recommends that vocational educational institutes adopt the use of ePortfolios into the curriculum. An ePortfolio offers the opportunity to provide a digital space to save apprentice’s resources as they progress through their schooling. An ePortfolio will also showcase the apprentice’s knowledge and skills to future employers and teachers.

As apprentices progress throughout their careers, it is often difficult to provide evidence of hands-on experience to employers. There are specific hands-on skills that companies expect from their employees and aside from a discussion, it is hard to prove that the skills have been attained.

As the formal schooling progresses throughout four years, concepts are expanded, and ideas are scaffolded on the previous year’s lessons. Many apprentices find themselves at a loss to prepare for the upcoming school year as they have lost, thrown out, or never fully understood their previous year’s resources.

Through the creation of an ePortfolio, an apprentice will be able to manage their resources in one place and will have access to the material at any time. After formal training is complete, the students may continue to collect information and evidence of work performed to show future employers examples of their knowledge and skillsets.

This case study will provide an analysis of the current problem being addressed. The evidence will support and offer alternatives that may be used to the curation of an ePortfolio.

As apprentices attend formal training, they are put in an academic situation that is not unlike college or university. Due to the hands-on nature of the training, it is often students who do not excel academically that pursue a career in the trades. This raises two issues of concern; assessment of skills and curation of information.

Assessment of skills

The formal vocational education system is tracked through academic grades rather than skills obtained. While it is acknowledged that theoretical study is important to a tradespersons education, it must also be recognized that hands-on skills are just as critical. Currently, there is no way for current or future employers to assess whether an apprentice has received the proper training in many hands-on skills. Typically, an apprentice spends approximately 80% of their time training on the job and the other 20% training in classroom-based training (“Apprenticeship basics”, 2017). When it comes to assessment, most of an apprentice’s skills are evaluated on how well they perform in classroom-based training.

Curation of information

Some apprentices pursue a life in trades due to difficulties they may have had in standard formal education (Taylor, 2010, p.505). By utilizing the same educational system, the system is setting some apprentices up for failure. Often the classroom-based training is a lecture-based lesson that may or may not be followed up with a lab to test the hypothesis of the lectures. The students are given resources such as textbooks, handouts, exercise books and lab books. It is often left to the student to take their own notes and curate their own information. As trades training builds on previous concepts from previous years, it may be necessary to go back to earlier resources for review. Due to the analog nature of these resources, they may be lost, illegible, or never fully understood in the first place.

For vocational education to continue to evolve in the 21st century, these issues need to be resolved. There is an alternative to the current structure of formal vocational training that will address both of these issues. This alternative provides an innovative approach that will benefit all stakeholders (Post-secondary institutes, government agencies, Employers and Apprentices) involved and will be discussed further in the next section of this report.

Alternatives

There are many different alternatives for the curation and showcasing of an apprentice’s knowledge and skills. The option this case is proposing is the use of a portfolio. A portfolio can be created by collecting notes, resources, and pictures and keeping them in a file. The other option would be of the digital variety, an ePortfolio, and would have various choices such as a website built on WordPress, Google sites, Evernote, or Mahara.

Design Criteria

Set of Design Principles

1. Let the students own it (Innovation). The students will design their own e-portfolio. The Artefact will be their design and they will decide what does and doesn’t belong. It will be made clear that this is a tool that can follow them during their apprenticeship and even into their careers.

2. Provide scaffolding and prompts (Impact on learning). This will be a scaffolded process. The students will be made aware of the definition of an e-portfolio. The students will be shown different alternatives and given prompts on how to build an e-portfolio that will be of use to them in subsequent years and further into their careers. As the student becomes more comfortable with the design and the process the instructor will become less involved.

3. Never lose their stuff (Reliance on technology). The use of an e-portfolio will help the students track their own education. The portfolio will allow them to save information to their system of choice. This could be a WordPress site, Google Sites, Evernote, or Marhara to name a few. It is important that the system is not part of a closed LMS but that the student have unrestricted access at any time to their own information.

4. Less is more (Usability). The design options for e-portfolios must be very minimalist. There must be a low learning curve to all the options given. The technology used should never be a barrier to the creation of an e-portfolio for any student. It is recognized that some students may be more adept than others in the use of technology.

5. Provide feedback (Risk). It is recognized that not all students will be comfortable in designing and building their own e-portfolio. It will be important to have assessment tools in place so that students may evaluate at any point where they are in the process. This may be done through examples given, or a daily check-in with the instructor at the beginning of the scaffolding process. As the students become more familiar with the design the assessment tools will be less available and less frequent so the student does not become too reliant on an assessment tool.

6. Always provide context (Value proposition of innovation in design). In the beginning, the design and lessons will be directed at a level that any student could create a useful artifact and understand its value. As the scaffolding progresses, the students will be made aware that they will not be the only ones using this tool. They must be aware that their own design must be accessible to others as well. It is important that the students are aware of the overall importance of an e-portfolio. As the lessons progress it must be made clear to the students the value of each new factor added to the artifact. There should be no point in the process that the student is left wondering why the step that is being addressed is important. The process of understanding the value of an e-portfolio could be important in subsequent years of schooling or as they embark on the career of their choice.

The use of the above six design principles was used when deciding on which platform to use. It was decided that Google sites will be used as they provide:

- A low learning curve (Principle’s #4 and #6).

- Flexibility in design (Principle #1).

- Access from anywhere with the internet (Principle #3).

- Integration with other Google tools such as Google Slides, Google Sheets and Google Docs. (Principle #3).

- Easy to build templates. (Principle #2).

- Ease of sharing with instructors for feedback. (Principle #5).

Recommendation and Implementation Plan

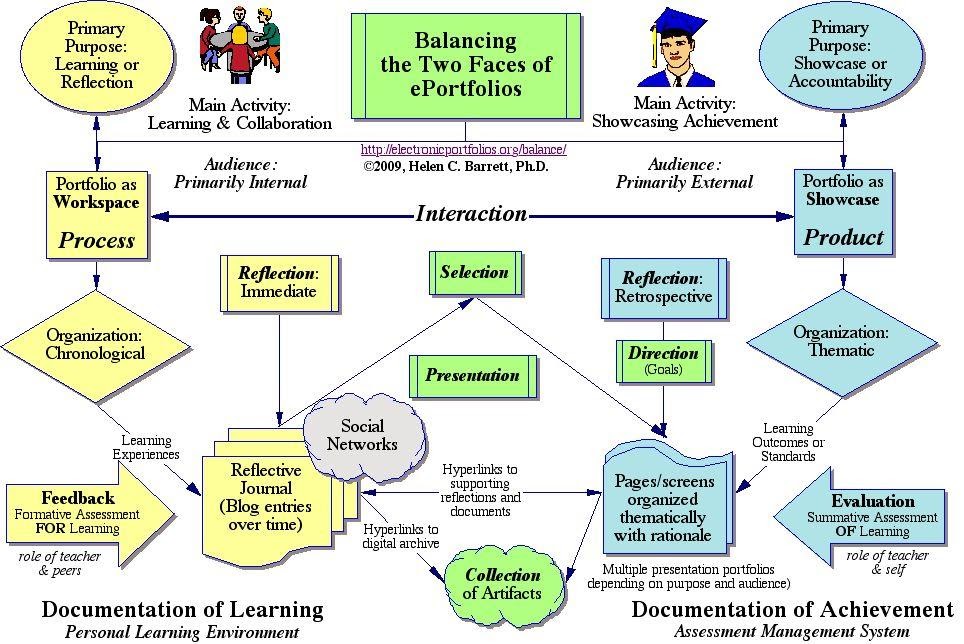

The creation of an ePortfolio through Google Sites will be beneficial to students on more than one level. Using Helen Barrett’s model for the two faces of ePortfolios (Figure 1.) it can be shown that not only will students be able to curate their own resources but that there is an opportunity to reflect and to fully come to understand the importance of what they are learning (Barrett, 2010, p.6). An ePortfolio will also allow the students to have a place where they can showcase their work and their experience.

Implementation Plan

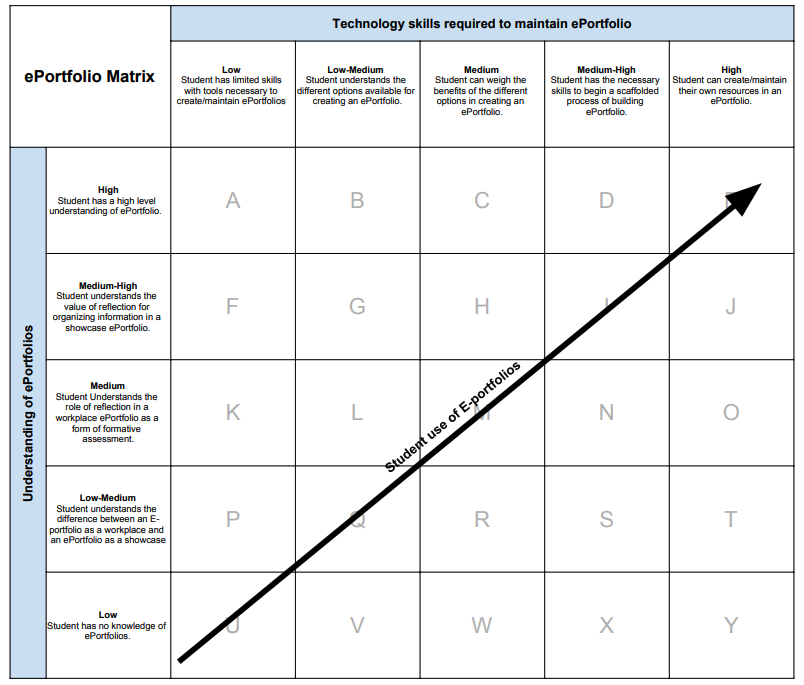

When implementing an ePortfolio, it must be realized that the artifact is as much a process as it is a product (Barrett, 2010, p.6). The students will be given a matrix that will guide them throughout the process (Figure 2.).

The process will begin with a detailed explanation of the purpose of an ePortfolio and its benefits. The students will be taught the basic skills necessary to build their own Google site. When this has been completed, the students will be given templates for each unit of the course. As Dron (2014) states, “templates provide the scaffolding to help less experienced learners to become competent and effective experts” (p. 257) These templates will provide prompts and rubrics for what is expected. As the apprentices progress through the course, the prompts will become less explanatory in nature and provide more of a guide as to what is expected. Throughout the units, the instructor will have “check-ins” with each student to allow for some time for guided reflection. At the end of each unit, the student will fill out a Google form to reflect on the learnings and how they can be applied to the student’s overall experience. Goldman et al. in their paper on design thinking discuss the importance of reflection in learning, “Design thinking supports this Freirean notion of impactful change which focuses on learning as a process where knowledge is presented to us, then shaped through understanding, discussion and reflection” (p.19) As the apprentices formal training progresses, the focus will shift from an ePortfolio as a workspace and shift towards an ePortfolio as a showcase (Exhibit 3). The students will be given time to reflect on how the information they have curated may be organized to showcase their knowledge and their skills. At the end of the course, the apprentice will have an artifact that not only curates their knowledge and skills but showcases them as well.

Conclusion

This post has addressed the issues that apprentices have in curating and showcasing their knowledge and skills throughout their formal education. With the use of Google sites, the students will be able to take ownership of their education and careers by creating an ePortfolio that they will have ownership over. In addition to their certificate, they can now provide a visual display of their skills and training during their apprenticeship.

Being able to say you can do something is one thing, being able to show that you are fully capable is another. An ePortfolio can be a powerful tool in a job market that may become competitive as more people explore a career in the trades.

References

Barrett, H. (2010). Balancing the Two Faces of ePortfolios. Educação, Formação & Tecnologias, 3(1), 6-14. [Online], Retrieved from: http://eft.educom.pt/index.php/eft/article/viewFile/161/102

Dron, J. (2014). Innovation and Change: Changing how we Change. In Zawacki-Richter, O. & T. Anderson (Eds.), Online distance education: Towards a research agenda. Athabasca, AB: AU

Goldman, S., Carroll, M. P., Kabayadondo, Z., Cavagnaro, L. B., Royalty, A. W., Roth, B., … Plattner, H. (n.d.). Assessing d.learning: Capturing the Journey of Becoming a Design Thinker. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-31991-4_2

Industry Training Authority. (2017). Apprenticeship basics. Retrieved from the Industry Training Authority website: https://www.itabc.ca/about-apprentices/apprenticeship-basics

Industry Training Authority. (2017). Vision and mission. Retrieved from the Industry Training Authority website: https://www.itabc.ca/about-ita/vision-and-mission

Statistics Canada. (2017). National apprenticeship survey: Canada Overview Report 2015.

Retrieved from the Statistics Canada website:

https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/81-598-x/81-598-x2017001-eng.htm

Statistics Canada. (2018). Registered apprenticeship training programs, 2016. Retrieved

from the Statistics Canada website:

https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/180528/dq180528c-eng.htm

Shared by:

Sorry, but comments are not enabled on this site.